Recognizing subtle sexism in advertising

Decades ago, an almost entirely naked woman could be seen advertising something not even remotely related, such as cigarettes, beer or a burger—exuding sex for the attention of the male audience. While sexism in today’s advertisements has become less overt, its subtle ongoing presence in modern-day mass commercial media continues to hold women back in society by marketing outdated feminine ideals.

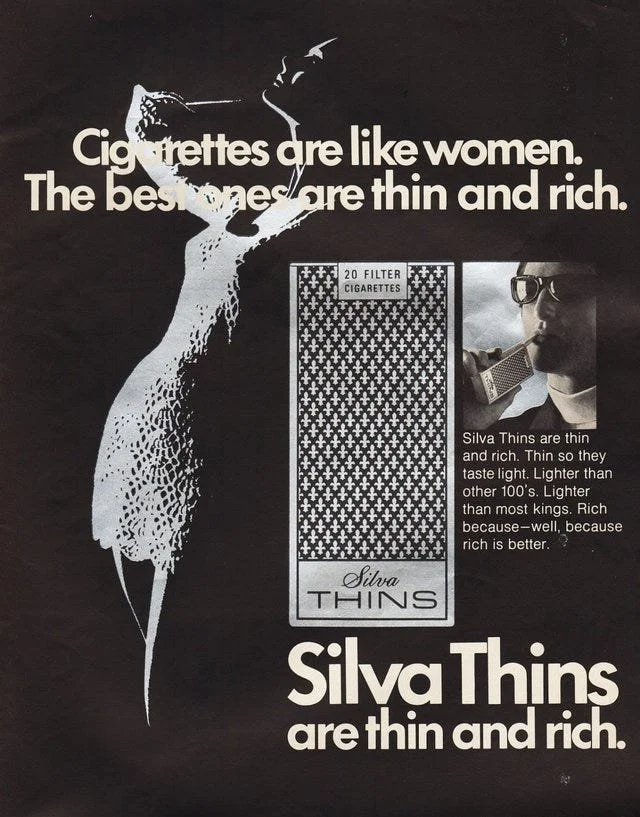

Advertisements often promote beauty standards for women. This Silva Thins cigarette advertisement from the 1960s shows a man enjoying their "thin and rich" cigarette, which conveys that women have to conform to certain expectations to please men.

Stereotypes create narratives of gender roles: what a woman should be, what they should value and most importantly, what they are valued for. The slogan stamped on Silva Thins cigarette advertisements in the 1960s, “Cigarettes are like women. The best ones are thin and rich,” doesn’t take much thought to decode—the value of women is dictated by superficial things, such as appearance. Expectations, such as those that link a woman’s beauty and her worth, then become internalized, making women ideal sales targets. The women in these ads are always wearing a smile, conveying the message that the product is selling a lasting happiness that can only come from achieving society's idea of beauty. The female audience believes they have to conform to society's gender norms, as displayed in advertisements, and buy certain products as a result. Advertisements tell women what is wrong with their appearance in order to then sell a product that fixes the supposed flaw, playing on their insecurities.

Advertisements also paint a picture of the social construct that is “femininity.” If an advertisement portrays a woman with shaved legs, as desirable in the male gaze, shaved legs becomes the feminine standard. The ultimate goal of marketing insecurities in advertisements is a never-ending cycle of profit; beauty standards are constantly changing, paving the way for new insecurities and therefore influencing people to continue buying products. There is an extreme juxtaposition between the purpose of the products being sold—to make women feel beautiful—and the effect of the advertisements—to feed into insecurities.

A perfect example of how both women and products are sexualized in ads, milk isn’t the focus of this ad—the naked model, Kate Moss, is. The caption also reads, “haven’t you heard that the waif look is out?” (waif meaning a thin, almost unhealthy looking person). Beauty standards are practically just trends in the world of advertising.

According to an article in Marketing Week, even today, around 25% of women in ads are sexualized to some extent, with 85% of them still being presented as the conventionally attractive “good girl.” By utilizing stereotypes, advertisements portray women mainly as either sex objects or caretakers, usually depicted as “good girls” in both cases. Women aren’t the only subjects being sexualized in ads; products are sexualized, because sex sells. A 2009 Burger King advertisement marketing their “BK Super Seven Incher” shows a woman with her mouth wide open, ready to eat the burger (though she doesn’t appear to be feeding it to herself). In bold print, it reads, “It’ll blow your mind away.” An ad like this would be banned in an instant nowadays, as the sexualization in it is quite obvious.

Concealing sexism through stereotypes is not always as obvious, however. In car commercials women are often seen driving young kids in family cars—exhibiting the caretaker stereotype. The mom is portrayed as a chauffeur; she solely tends to her kids. On the other hand, men might be shown driving alone on a long, open road, conveying freedom. Take Matthew Mcconaughey, the face of Lincoln, who was named People Magazine’s “sexiest man alive” in 2005. In a 2014 Lincoln MKC commercial, Mcconaughey radiates power as he drives solo down a winding mountainous road, in a tuxedo with one hand on the wheel. Where the women in car commercials are often portrayed as mothers of wives, the men are unconfined.

Details as minute as color palettes can often be sexist. Pastels, normally associated with women's products, are more submissive and youthful—as seen in the Marc Jacobs Daisy perfume ad. Dark colors, associated with men, convey power—as seen in the Chanel No. 5 fragrance ad.

While men have been objectified in advertisements as well, they are still generally portrayed with power. Half-naked men can be seen pinning down women in several Dolce & Gabbana and Calvin Klein advertisements selling cologne—promising power and sex-appeal to their male audiences. Whereas masculinity conveys strength, femininity is depicted as submissive. Unlike men, women are told to change themselves in order to achieve beauty and happiness.

Now commercials empowering women have become more plentiful, promoting body positivity and depicting women as strong. But just because sexism in advertising has become less blatantly obvious, doesn’t mean there isn’t sexism—it’s just sneakier.